Doré so desperately wanted to illustrate the Divine Comedy (find in our collection of 700 Free eBooks) that he financed the first book in 1861 with his own money.Īfterwards, as Mike Springer wrote in a previous post on Dore’s illustrations, his publisher Louis Hachette agreed to put out the next two books with the telegram, “Success! Come quickly! I am an ass!” Doré’s eerie, beautiful drawings are just one such set of famous illustrations we’ve featured on the site previously.Īnother artist perfectly suited to the task, William Blake, whose own poetry braved similar heights and depths as Dante’s, took on the Inferno at the end of his life.

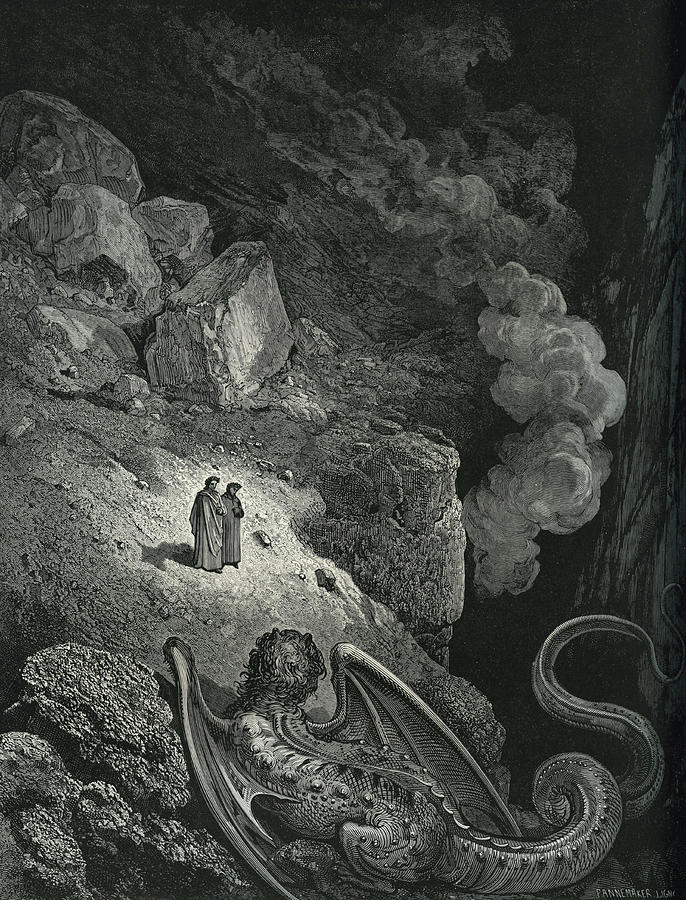

In prolific French artist Gustave Doré’s rendering of the ninth circle scene, above, Satan is a huge, bearded grump with wings and horns. Like the rest of us, artists have been drawn to Dante’s extraordinary images and extensive fantasy geography since the Divine Comedy first appeared (1308-1320). Like Achilles dragging Hector behind his chariot in Homer, who can forget the lake of ice Dante encounters in the ninth circle of Hell, in which (in John Ciardi’s modern translation), he finds “souls of the last class,” which “shone below the ice like straws in glass,” and, frozen to his chest, “the Emperor of the Universe of Pain,” almost too enormous for description and as hideous as he once was beautiful. While the Mad Men reference may be the more literary, the former two may hint at the more prominent reason the Inferno has captivated readers, players, and viewers for ages: the lengthy poem’s intensely visual representation of human extremity makes for some unforgettable images.

For a book about medieval theology and torture, filled with learned classical allusions and obscure characters from 13th century Florentine society, Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, first book of three in his Divine Comedy, has had considerable staying power, working its way into pop culture with a video game, several films, and a baleful appearance on Mad Men.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)